For those who have experienced it, a trip to a hand-pulled noodle (lamian 拉面 in Mandarin) shop is a culinary highlight of China. Often these shops are named after their product: “beef noodles”(牛肉面), or “Lanzhou pulled noodles” (兰州拉面). In China, many of these shops are run by Chinese Muslim families, as the noodle is particularly famous in the Chinese Muslim (aka Hui) heartland of central China. Expert noodle cooks pull noodles per order, thick or thin. Generally you can watch the cooks as they pull, so you can see for yourself how fresh the noodles are. They certainly make it look easy! Try to do this at home however, and you’ll find it all but impossible. You pull the dough and it will break, repeatedly. How do they do it? Here I highlight some of the issues in trying to pull your own noodles.

A bowl of beef noodles from Philly’s Nan Zhou Hand Drawn Noodle House

First of all, you have to see it to believe it. Here are some links to some videos: a clip from a much loved CCTV documentary called 舌尖上的中国 “A Taste of China”, acrobatics and pulling noodles through the eye of a needle (in Mandarin with a bored daytime TV host).

Second of all, you need to eat it for yourself. So that you know this is worth obsessing over. In Philly, you should try the one pictured above. For me, it is a near-religious experience.

Flours have a different gluten contents. Some flours are better for pulling noodles than others. East Asian flours have less gluten than typical U.S. all-purpose flour. Luke Rymarz, an unusual hobbyist in noodle-pulling, has an excellent site where he explains his testing of flours. He has a recipe to emulate East Asian wheat flours for the best pulled noodles. That, along with very useful step-by-step pulling instruction videos, can be found at his site. Too much gluten will make the dough hard to pull, and a lot of manual (or machine) labor is crucial to beat the dough into a clay-like or silly putty-like consistency. The idea is not to massage the dough to build gluten, but rather to beat it up and knead it into submission.

Noodle dough needs some time to relax. If you notice, noodle cooks take a chunk of dough out of a bin where a bunch of pre-sized doughs are resting. Dough needs to relax before it becomes elastic.

A little alkaline can help give some elasticity to the dough. Alkalines can be added as a solution or powder, but in very small quantities. This step is actually optional, and in some noodle-pulling traditions (in Xinjiang for example, with the classic Uyghur dish laghman) noodle recipes are simply flour, water, and a little salt.

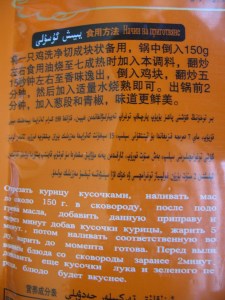

Alkalines are often cited as the “secret ingredient” in hand-pulled noodles. Lye water, or particular mineral waters are often used. For noodles in central China (Gansu, Shaanxi), of the Lanzhou tradition, the alkaline of choice is penghui (蓬灰). This is made by taking a local tumbleweed (bitter fleabane) and burning it into ash. The resulting powder is added to water to create a solution that is then rubbed onto dough before pulling. This so-called “secret” was “exposed” on Nanjing TV in 2011, apparently leading to much anger among noodle restaurant owners. Penghui has long been used for Lanzhou lamian, and it is hardly unknown. Pulling noodles at home is however, a very labor-intensive process, with or without penghui. Restaurant owners should have very little to fear that their business would end with people making their own at home.

Back in the ’90s when I was teaching English in Guangzhou, a colleague at the school learned I was interested in learning noodle pulling. She had a relative in central China send a bag of penghui. I used it, and the dough was made more elastic by applying the solution during kneading. I frequently used too much of it however, and the noodles had a kind of sulfury taste too them. Now when I eat lamian in China, I can detect this flavor at certain shops.

I have yet to find penghui for sale in the states. It is of course for sale in China, here is a link to a search on taobao.

[UPDATE 19Sept2017]: See a much longer post on the theme of Lanzhou-style pulled noodles and issues with noodle pulling: “Lanzhou pulled-noodles, Lanzhou-style”

If you haven’t yet tried hand-pulled noodles, places are popping up in the U.S. We are lucky in Philadelphia to have two specialized hand-pulled noodle restaurants, Nan Zhou Hand Drawn Noodle House, and Spice C Hand Drawn Noodle, both in Philly’s Chinatown. I don’t detect the taste of penghui at our local establishments, but they do serve up delicious Lanzhou-style noodles.