Sorghum is a hearty (and delicious!) cereal crop that originated in northeastern Africa some 5-6000 years ago. Already in ancient times it was propagated across Persia and India, and by the time of the Mongol Empire it had become an important crop in parts of Central Asia and China. Today in China, sorghum (gaoliang 高粱) is still a major crop and is perhaps best known for its role as a preferred grain in distilled alcohol. Several classic baijiu 白酒 brands harness the sugars of sorghum, like Guizhou’s famous Moutai 茅台, and Wuliangye 五粮液 from Sichuan.

But this grain is also a crucial subsistence food in very hot and arid regions across Eurasia–from Turkmenistan all the way to North China. Sorghum, alongside foxtail and broomcorn millets, has evolved to thrive even in desert regions, where grains like wheat and rice have trouble surviving. Unique foods based on this grain have evolved over the millennia, and became especially important in times of food scarcity.

Sorghum’s plump grains are rich in starch, and they boil well for pilaf or porridge preparations. The grains can also be ground into flour, which is usually mixed with a small portion of wheat flour to make dense and hearty breads and chewy extruded noodles. There is a faint bitterness in the aftertaste, but that pairs incredibly well with savory soups, stews, and sauces.

I started exploring sorghum with a sort of pilaf preparation, together with mung beans, inspired by the delightful 2019 cookbook by Gyulshat Esenova Sachak: Traditional Turkmen Recipes in a Modern Kitchen. In the cookbook this dish was called an etli köje (“porridge with meat”), but the grains are boiled and cooked through, just shy of bursting. The grains have an aftertaste with just a hint of bitterness and the accompanying sauteed lamb and carrots and gatyk yogurt were a perfect match.

Recently I’ve been working through some old Uyghur script documents from the Gunnar Jarring collection on “the food and drink culture of Alteshahr (present day Tarim basin in Xinjiang)”, dating from around 1905-10. Sorghum appears prominently as an everyday grain (called qonaq “corn” in the text), alongside barley, wheat, maize (called kömmä-qonaq in the text), and rice. Presumably sorghum foods were more prevalent a hundred years ago in the Tarim Basin, but nowadays they aren’t exactly mainstream foods. You are unlikely to find these at restaurants.

Further west, Bahriddin Chustiy, the celebrated Uzbek chef and restaurateur included a recipe for sorghum bread (jugara non) in his 2020 cookbook Non, on the theme of Uzbekistan’s diverse flat breads. In the book he describes the bread as being not well known–he himself only encountered it for the first time when he traveled to Uzbekistan’s dry western regions of Karakalpakstan and Khorezm. Again, while this bread is now lesser known in mainstream Uzbek food culture, it was important in rural areas where wheat and rice were scarce.

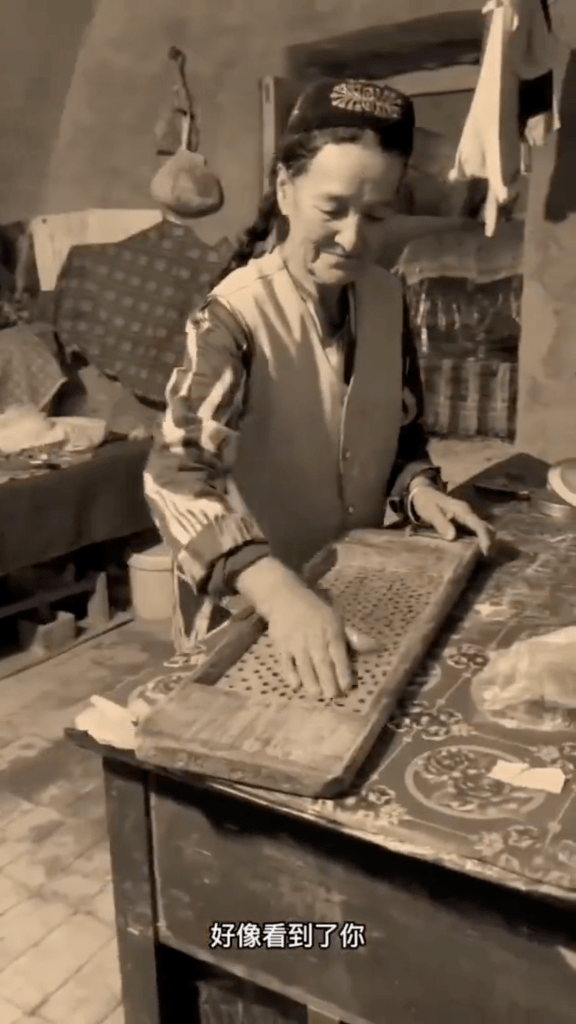

In regions that grow the grain, sorghum flour is often blended together with wheat flour to make sorghum bread. The image on the left is an example of that, a still image taken from one of the many WeChat videos posted on the account of Tayan读书会, a Turpan-area content creator. His videos often show many steps involved in producing breads such as these, what he calls “blended naan” or qoshuqluq nan قوشۇقلۇق نان.

The names that this grain are known by across Central Asia hint at South Asian introductions. In Turkmen they call this jöwen or jugara, in Uzbek and Tajik it is jo’xori and ҷуворӣ. In Kazakh it is қонақ жүгері. Most of these names are very close to the Hindi/Urdu juwar. Contemporary Uyghur is a little bit of an outlier with aq qonaq ئاق قوناق “white corn”. Like the Uyghur colloquial name, in broader Central Asia, sorghum is has several name variants that are similar to the word for maize. The two plants do resemble eachother.

Sorghum, bitter and nostalgic flavors of hardship

References online and in books often present sorghum foods with a hint of nostalgia, particularly for regions of Asia that experienced some hardships in the past 50 years or so. This was the grain that the elders ate when wheat and rice were scarce. It was a taste of hardship but also of self-reliance.

This nostalgia can be seen in a 2018 video on CCTV’s YouTube channel of a show called “Unveiling the Secrets of China: Exploring Xinjiang” 《中华揭秘》寻味新疆 where a 34-year old Turpan man named Alim collects sorghum from a friend’s farm and processes it into flour for tonur breads and a sorghum gruel that “only the old folks know” to eat with his family with a lamb and savory root vegetable stir fry topping. The high definition video shows the plant and its grains in detail, and shows the process of his family baking sorghum naan too.

Recently a friend sent me a social media music video by “Kariz Äpändi” 坎儿井先生, a Turpan-area WeChat content creator that featured nostalgia of a difficult bygone era where elders made a style of extruded noodle that was called tüshük pän läghmän تۈشۈك پەن لەغمەن. In the video the singer finds his grandmother’s noodle board and noodle press and memories flood back to him depicting her pressing large noodles above a qazan of boiling water. After draining the noodles and dressing them she takes them to her husband who is toiling in the field, where there is also a baby in a cradle (possibly the singer?). Although it wasn’t strictly highlighted in the video, this type of extruded noodle was commonly done with sorghum flour, mixed with a little wheat flour. A friend from the Turpan region confirmed this was common up through to the 1990s or so, when wheat was still expensive for many in the villages around Turpan. The following are image stills taken from the music video posted in WeChat on Dec. 2nd, 2023:

Extruding sorghum noodles and making läghmän (with non-pulled-noodles)

I was inspired to test these noodles out. I invested in a cheap German spaetzle maker with two size options to act as my noodle-extruder.

Note: läghmän doesn’t necessarily mean “pulled noodles”. A lot of people assume that is a borrowing from the Chinese lamian 拉面, meaning “pulled noodle”. I’m in the camp of those who think this borrowing is more likely from liangmian 凉面 meaning “cooled noodle”, that is, a noodle that is boiled and then immersed in cold water after cooking. Coincidentally, the word langman, spelled لانكمن (an alternate spelling of the beloved noodle dish) is mentioned among the list of common wheat flour dishes in the Jarring Alteshahr document referenced above. So far this is actually the earliest reference I’ve encountered in a text. In older documents noodles are frequently mentioned by many other Turkic names, but not läghmän/längmän. I am supposing that this word became commonly used in Xinjiang during the Dungan migrations across Xinjiang over the 18th and 19th centuries.

My experiments to create noodles without wheat flour were also inspired by the most antique noodles yet found in archaeology, dating from way back to nearly 4000 years ago, from what is now China’s Qinghai province. Those ancient noodles were made from millet, which would have a very similar starch and texture to the sorghum used in my experiments. Someday, after I find some nice millet flour, I’ll try to make some millet noodles as well.

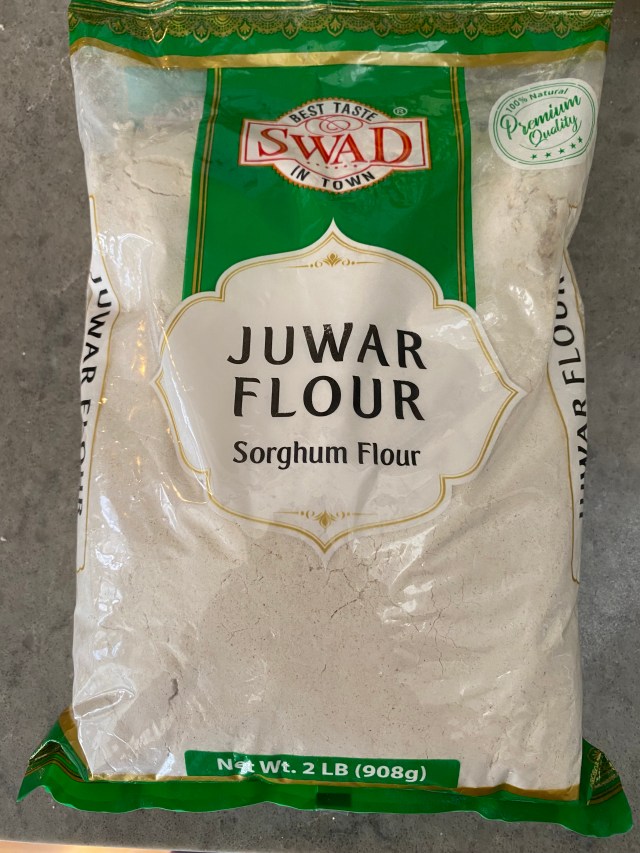

My first try was a bit of a disaster. I attempted to grind my own sorghum flour with a blade grinder and mesh strainer. I simply could not get the flour fine enough–noodles just disintegrated as they hit the water. Days later I found finely ground sorghum flour from Patel Brothers in Bensalem, PA (see left), and that worked MUCH better.

I first tried to replicate what I saw in that nostalgic Uyghur music video, starting with 100% sorghum, a little salt, and very hot water to mix the dough. I was able to squeeze out fat noodles into the boiling water, but they promptly dissolved into a porridge. Another disaster.

Then I continued with online search queries. It turns out 100% sorghum noodles are kind of a healthy food trend today in southern India. There are several videos online showing how to steam noodles to be used to make a popular Indo-Chinese stir fried noodle dish in India known as “Hakka noodles”. These instructional videos (see here for one, and here for another) were incredibly helpful for me to figure out a good noodle consistency, and to make this work for läghmän.

After studying those videos I then tried to extrude noodles into a steamer basket and steam for 20 minutes, like the Indian vloggers were doing. That ended up working much better, but only for the fatter noodles. The finer 100% sorghum noodles were still too crumbly.

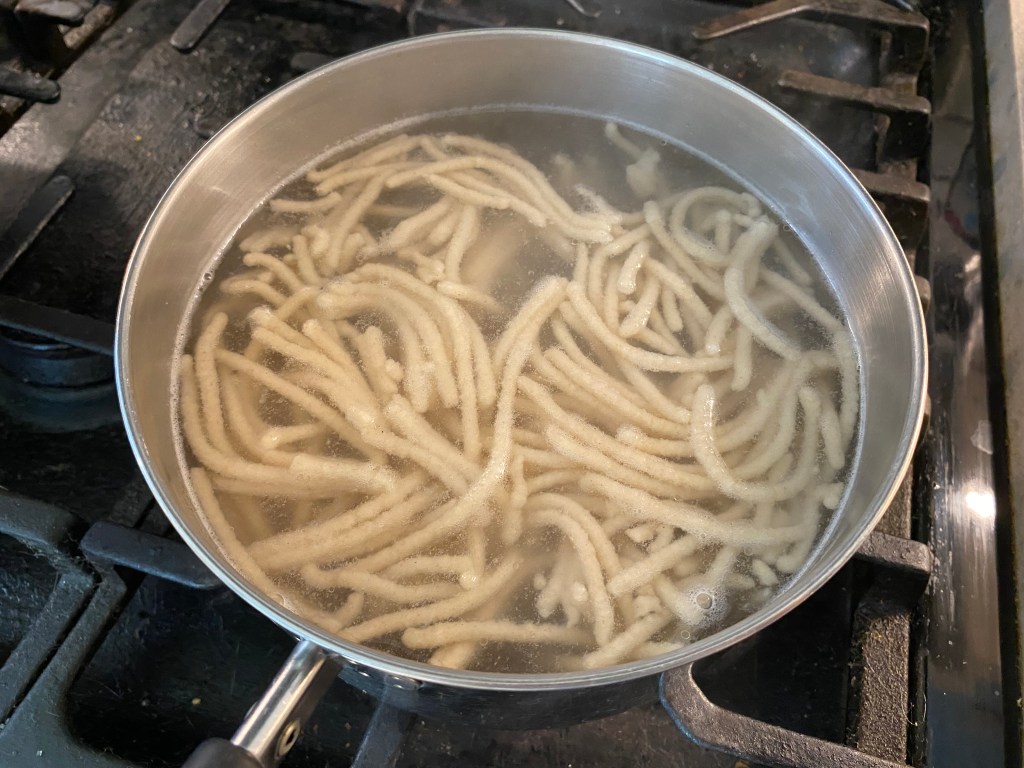

I then tried different ratios of mixing with all purpose flour. The following was 50/50 sorghum and all-purpose flour, and I extruded thick noodles directly into boiling water (probably the closest version to the nostalgic video I was emulating). I have to say, the results were not bad:

That boiled large noodle was finally getting pretty good. But I still had some experimenting to do, aiming for finer noodles. I continued with steaming, and a ratio of 3/4 sorghum flour to 1/4 all-purpose flour, extruded first into a steamer basket, and then steamed for 20 minutes. I think this one was my favorite. The noodle texture was quite similar to a rice noodle or spaghetti, and the noodles seemed to gel well in the steamer:

In all experiments with steaming, I had to let the noodles cool down before very gently breaking them up. Sticking was a bit of a problem, and perhaps there is further experimentation to be done with adding oil at some point to help noodles not stick together. Once noodles were cooled and separated, they could easily be mixed with a hot topping.

All experiments were topped with lamb and ingredients from my local farmer’s market: celery, potatoes, garlic scapes and tatsoi. Basically this was a home-style läghmän topping (see here for another example of that from a much older post).